Cash Flow vs. Profit: Everything You Need to Know

Cash Flow vs. Profit

Profit is the revenue remaining after deducting business costs, while cash flow is the amount of money flowing in and out of a business at any given time. Profit is more indicative of your business’s success, but cash flow is more important to keep the business operating on a day-to-day basis. Over the long term, lack of profit has a negative impact on cash flow.

One of the most important things about small business accounting is understanding the difference between cash flow vs. profit. Many entrepreneurs start businesses with the goal of turning a profit. But what they don’t realize is that cash flow is what keeps the lights on.

Imagine this hypothetical: You meet with your accountant at the end of the year to review your tax return and they report that your business turned a sizable profit. While this is good news, you can’t help but be surprised. Why? Because there’s no cash in the bank and you have no idea how you’re going to pay the income taxes on the profit.

This happens more often than you think: Businesses turn a profit while being cash flow negative, and others have lots of cash flow and no profit to show for it. How can a business turn a profit yet not have any cash at the end of the year? To help you understand, we’re going to break down the key differences between cash flow vs. profit. We’ll also provide you with some examples that illustrate the difference between cash flow vs. profit, and make some recommendations on the accounting basis your business should use.

But first, let’s get our definitions straight.

What Is Profit?

Profit is one of the key metrics used to determine a business’s success. It is defined as the amount remaining after deducting the costs needed to generate revenue. In other words, if your monthly revenue is $10,000 but it cost your business $8,000 to generate that $10,000, then your profit margin for that month is $2,000.

However, not all types of profit are created equal, or equally reflect your business’s true profitability. There are generally two different types of calculations used to illustrate your business’s profit: net profit and gross profit. Let’s learn a bit more about both:

Gross Profit

A company’s gross profit is the profit it makes after deducting the costs directly associated with making its products or providing its services. It is calculated by subtracting your business revenue from the “cost of goods sold” (COGS). COGS refers to all expenses that you can fully and directly attribute to the production of goods sold by a company. For example, if you operate a retail company, COGS is the cost of inventory sold in your store.

Net Profit

Net profit is a more accurate reflection of your business’s profitability than gross profit because it factors liabilities beyond COGS. Net profit is found by subtracting COGS, operating expenses, and interest and taxes from your revenue. Operating expenses include things like payroll for your employees, rent on a retail space, loan payments, and any other expense not directly attributable to the production of your business offering.

Interest and taxes include federal, state, and local income and payroll taxes, as well as any interest owed on business debt—like a business loan.

What Is Cash Flow?

While profit is the goal, cash flow is a better metric to determine your business’s short-term and long-term outlook. In a word, cash flow is the net amount of cash moving into and out of a business at any given time. Note that the key word here is “time.” Cash flow can only be understood through the lens of a given timeframe. Most businesses track cash flow on a month-to-month basis.

Cash flow positive is when you have more money moving into the business than you have moving out at any given time. Cash flow negative is the opposite—the amount of money you have going out of the business is greater than the amount of money you have coming in.

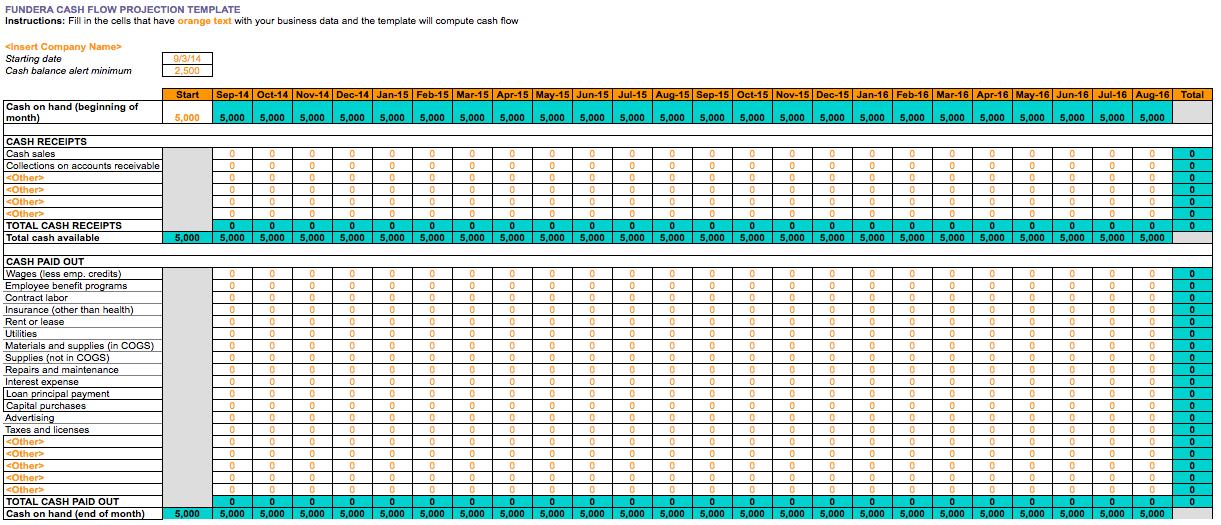

To determine your business’s cash flow, you’ll need access to a cash flow statement template. Start by adding up all your cash on hand at the beginning of the month and putting it in the box in the upper left-hand corner. Next, you’re going to fill in your cash inflows and cash outflows—your operating, investment, and financing activities. Remember though: We’re talking about cash—not invoices or purchases.

In other words, if you send an invoice in June that isn’t paid in September, you’ll mark that as “collections on accounts receivable” in September. Similarly, if you pay for a purchase on a business credit card in April, but don’t pay the credit card statement that includes that purchase until May, you’ll mark the expense in May—because that’s when the cash outflow actually took place.

After you input all of your cash inflows and outflows, if your closing balance (in the last row) is higher than your opening balance (first row), you’re cash flow positive for that month. If it’s lower, your cash flow is negative.

Cash Flow vs. Profit: Income and Expenses

Now that we understand the definitions of both terms, it should become clearer what the difference is between cash flow vs. profit. A company can have positive cash flow while having no profit if the cash comes from sources other than income, such as when an owner puts in their own money or if they take out a loan. These types of transactions aren’t income but rather liability or equity transactions that appear on the balance sheet.

Conversely, a company can have negative cash flow while having a large profit if the owners take cash out of the business to pay personal expenses or use it to make investments or loans to others. These types of cash out transactions are also reported on the balance sheet, not the profit and loss statement.

The difference between cash flow and profit really comes down to the source of cash transactions and the basis of accounting.

Cash Flow vs. Profit: Basis of Accounting

While the source determines whether the transaction is categorized as income or an expense, the basis of accounting determines when you report income and expenses, and greatly affects the amount of profit you report for a period of time. There are two general basis of accounting methods: accrual and cash. Let’s explain each one.

Accrual Basis of Accounting

Accrual basis of accounting recognizes revenue and expenses when they are incurred. In other words, when the money is actually received is irrelevant. Thus, accrual basis of accounting is only concerned with when the income and expenses happened.

Cash Basis of Accounting

Cash basis of accounting is the opposite of accrual basis of accounting. In cash basis accounting, revenue is only recognized when it is received and expenses when they are paid—not when the revenue is earned and the expenses are incurred. In other words, when the income or expense hits your account is what matters.

Many business owners use cash basis of accounting to gauge the profitability of their business. But this can be a big problem if your company extends credit to your customers or uses credit to finance your purchases because those transactions won’t be reflected in the bank account activity until they are paid.

If your company uses credit, you likely use a spreadsheet or double-entry accounting system (like QuickBooks) to keep track of what your customers owe you and how much you owe to your vendors. These invoices and bills are recorded in the accounts receivable and accounts payable ledgers, respectively. As you receive or make payments, you mark the invoices and bills as paid in the ledgers and reduce the balances. Accounts receivable and accounts payable are both reported on the balance sheet.

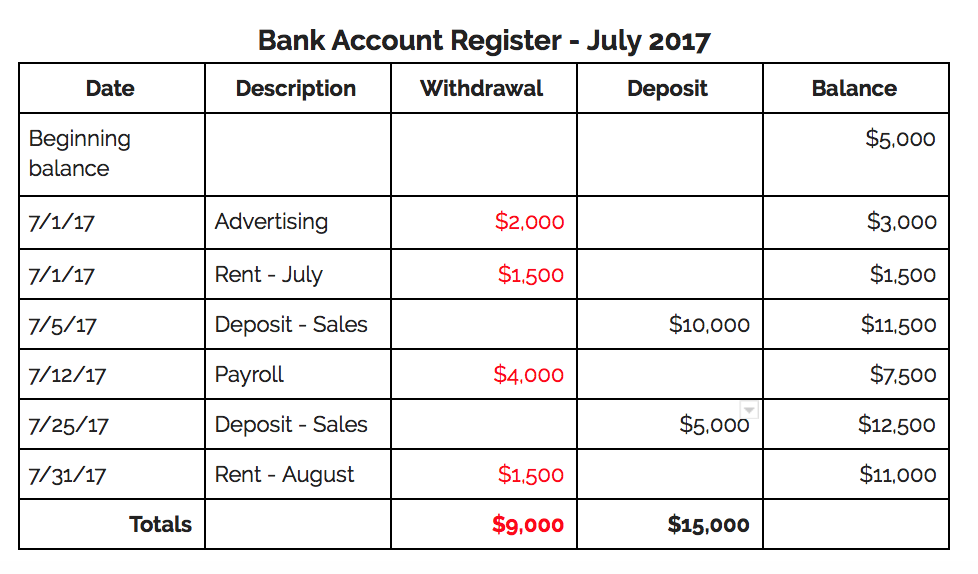

In order to understand how the accounting basis of transactions could affect your profit for a period, let’s take a look at an example. In our example, your business account shows the following checks and deposits for the period of July: We can see that the company deposited $6,000 more into the bank account than it spent for the month, which increased the cash balance to $11,000.

We can see that the company deposited $6,000 more into the bank account than it spent for the month, which increased the cash balance to $11,000.

Now, let’s take a look at how these transactions are reported on both a cash and accrual basis:

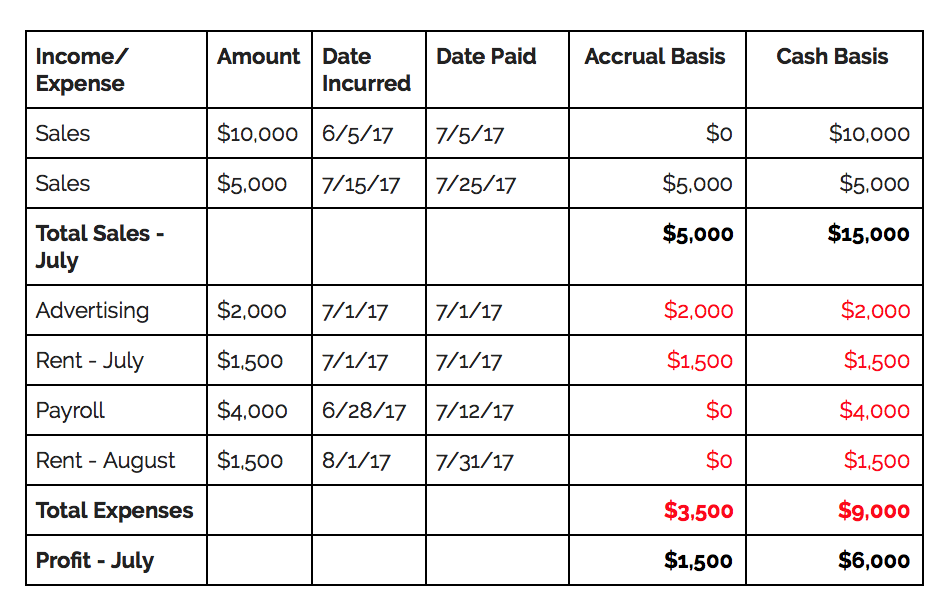

Notice that the profit on an accrual basis is significantly lower than the cash basis profit. Let’s take a look at the differences and how the profit could be so different:

Notice that the profit on an accrual basis is significantly lower than the cash basis profit. Let’s take a look at the differences and how the profit could be so different:

- The $10,000 deposit on July 5 was actually payment for a sale that occurred in June and would have been included on the June profit and loss statement.

- The same is true for the payroll paid on July 12 that was for the pay period ending June 28.

- The rent payment made on July 31 isn’t included on the profit and loss statement for July because it is a prepayment of the August rent and will be included in the August profit and loss statement.

You can see how the basis of accounting can really make a difference in the reported bottom line of a business and its profit. It’s important to know whether your business reports its income to the IRS on a cash or an accrual basis on your tax return. If you run your business on a cash basis but report to the IRS on an accrual basis, you can bet there will be differences. Make sure you know what to expect by working with a qualified tax professional.

Cash Flow vs. Profit: The Bottom Line

When comparing cash flow vs. profit, keep in mind that profit is the revenue remaining after deducting all costs associated with operating the business, while cash flow is the amount of money flowing in and out of a business at any given time. Therefore, the key difference between cash flow and profit is time. Profit can’t show you the whole picture of how your business is doing financially because profit doesn’t tell you when those inflows and outflows of cash are coming. In other words, it can’t give you a day-to-day understanding of your business’s financial well-being.

In short, profit can show you how successful your business is, but it can’t tell you if your business has the money to survive long-term. On the flip side, an unprofitable business that is cash flow positive will have a hard time remaining cash flow positive for long.

Now that you understand the difference between cash flow vs. profit, you can go about managing your small business’s accounting more responsibly and ensure that your business is growing in a sustainable way.

11 Accounting Terms All Business Owners Must Know to Succeed

Heather D. Satterley

Heather Satterley is a contributing writer at Fundera.

Heather is founder of Satterley Training & Consulting, LLC, a firm dedicated to helping accounting professionals learn and implement QuickBooks and related applications. She works with sole practitioners and teams to streamline internal processes as well as consulting on a variety of client engagements.

With over 20 years experience as a bookkeeper, accountant and enrolled agent, Heather has helped thousands of small business owners and accounting professionals sharpen their skills and increase their confidence with accounting technology.

As a member of the Intuit Trainer/Writer network, Heather teaches QuickBooks to accounting professionals all over the country via live training events, webinars, and conferences.

Featured

QuickBooks Online

Smarter features made for your business. Buy today and save 50% off for the first 3 months.

Related Posts

- Current Assets Formula: What It Is, Calculation, and Example

- Divestiture Definition: What Is Divestiture in Business?

- Certified Business Appraisal: What It Is and Why It Matters

- Financial Statements: The Ultimate Guide to the 3 Key Financial Statements

- The Keogh Plan: Saving for Retirement While Self-Employed